Confirmation bias is defined as the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of one's existing beliefs or theories. It’s a very natural human (and animal) trait, one at the heart of social media’s success, and most likely an evolutionary one. It is crucial to our brain’s ability to quickly compartmentalise and prioritise millions of pieces of information in order to make decisions. It also helps us influence people and perhaps even be influenced (read ‘accepted’) by other people.

The aim of this article is to not only demonstrate how pervasive and powerful confirmation bias is within the real estate industry, but importantly how we might go about mitigating it without falling foul of other biases along the way; namely Precision Bias and Herd Mentality.

For those of you who already believe in confirmation bias, this will be an easy sell. Those of you that don’t will be harder to convince, thereby inadvertently making my point for me. So, thank you in advance.

Precision Bias

“Facts are stubborn things, but statistics are pliable”, Mark Twain

One way of heading off confirmation bias might be to use lots of numbers. There is power in numbers, in that they promote plausibility and imply both accuracy and attention to detail. Wouldn’t you have more faith in a business if they were to say “We are going to increase EBIDTA by +17.39% over the next 15 months” rather than “We are going to boost profits over the next year or so”? Numbers with decimal places must surely have come from a carefully-constructed model, whereas sweeping generalisations could have come from a long boozy lunch on a Friday afternoon. And crucially for this discussion, numbers also tend to imply impartiality.

Context is everything, of course. Now synonymous with market research, Whiskas long-running slogan originating in the 1970s would not have been as memorable – at least not for the same reason – if they had gone with “79.61% of owners said their cat prefers it”.

"People don't buy for logical reasons. They buy for emotional reasons”, Zig Ziglar

“But we’re investors not marketers”, you protest. Like it or not, there is an element of sales in everything that we do. If we cannot get our colleagues or clients to buy into what we are saying, having a proven predictive multiple linear regression model isn’t going to help. Many a time have I simplified several days’ quant work into a single slide or, to put it another way, changed “+17.39%” into “boost”. Colleagues and clients that know the quality of your work, have seen the results based on your guidance, or at times peeked under the bonnet of your quantitative models when they were curious and time-rich, will trust you when you say “boost”.

The essence of this section of the article, however, is to remind us that numbers are as pliable as words, and can be manipulated, either intentionally or unintentionally. Like words, they can be misunderstood by those that don’t speak their language. And as with words, some people will use far more than is necessary to get their point across.

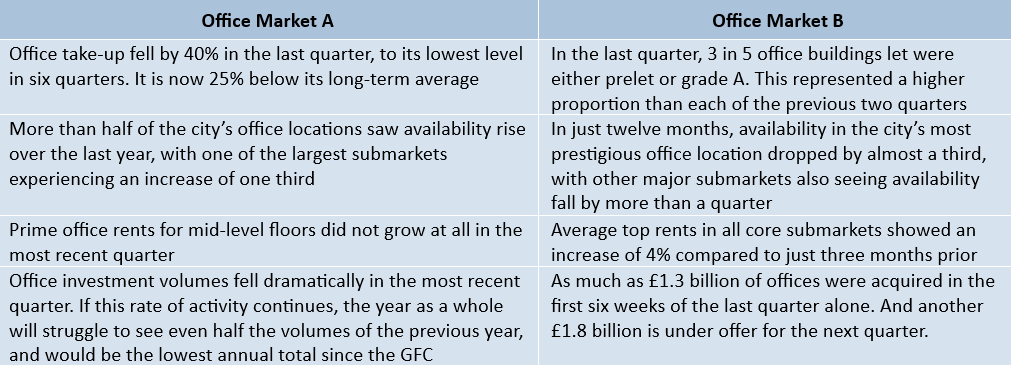

Just how susceptible are numbers to confirmation bias? Please scan the following comments on two office markets, and consider which of these is the stronger market from an investor’s point of view.

Unless you are a counter-cyclical investor, I imagine that you preferred Office Market B. After all, to paraphrase, rising demand and falling availability have resulted in higher rents and more investment activity. By contrast, Office Market A saw demand decrease, availability rise, and although rents didn’t fall, investment activity certainly did.

Would you believe me if I told you that the data behind these comments are both real and from the same market. They are also from the same single source, Colliers’ London Offices Snapshot, Q1 2023. The interpretation of the data is my own, not Colliers’, and purposefully skewed both positive and negative to make a point.

“Auggie can't change how he looks. Maybe we should change how we see”, Wonder

Whilst there may be specific intent behind how some market trends are presented, an agenda that is identifiable is not necessarily problematic as the reader can factor this in. For example, for brokers whose revenues are somewhat dependent on market activity, one might expect their reports to have an optimistic slant. So, not problematic unless perhaps AI is reading reports on your behalf (See my previous blogpost Is AI mightier than the pen?).

More challenging to detect are the subconscious confirmation biases which we all have but may not be aware of. Determined sellers of London Offices may unwittingly interpret raw data as per the Office Market A commentary above, whilst come-what-may buyers of London Offices might find themselves naturally aligning with an Office Market B style interpretation.

Herd Mentality

“If everyone is thinking alike, then somebody isn't thinking", General George S. Patton

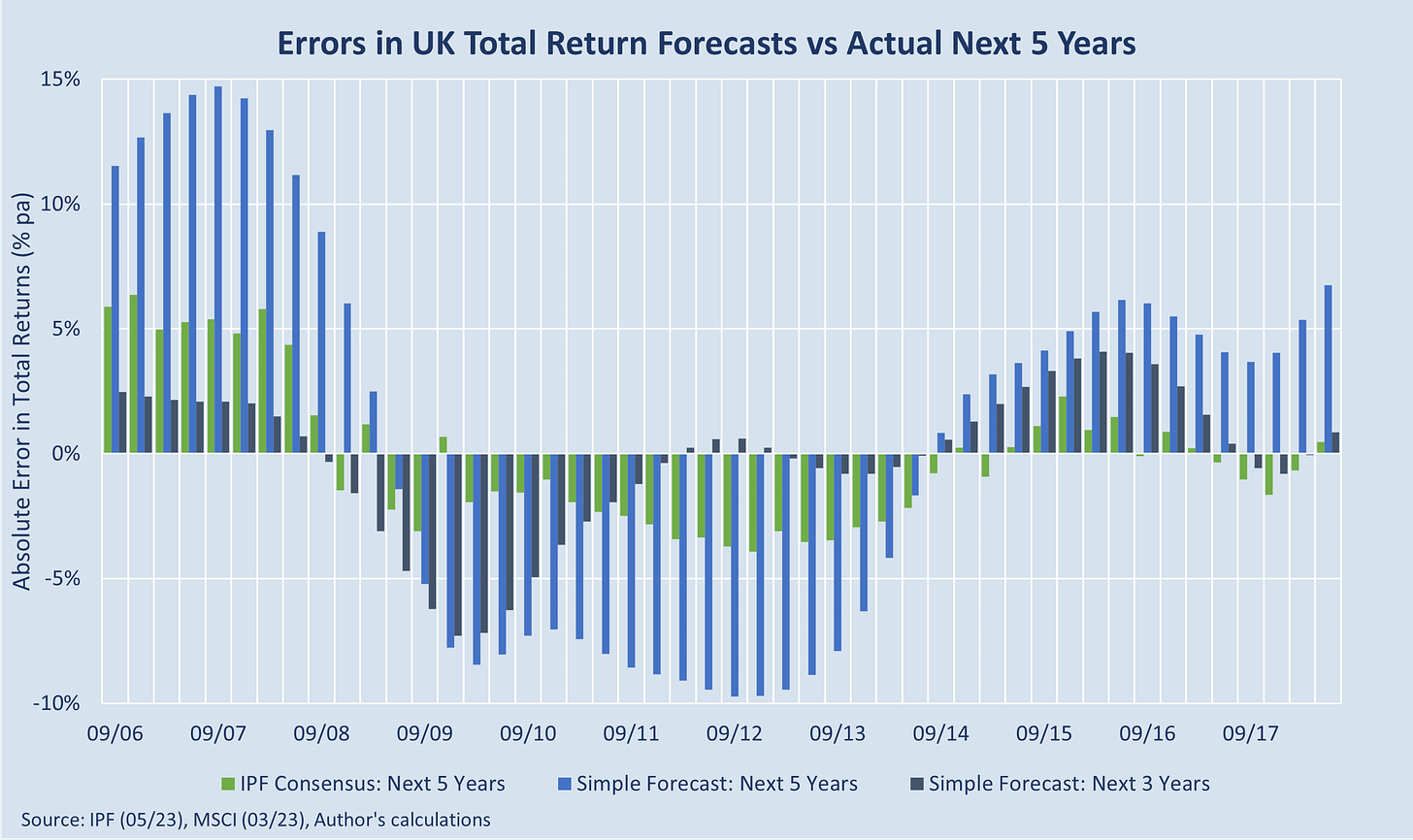

Another defence against the accusation of confirmation bias is that one’s view is mainstream, and so therefore not a product of self-deception. Everyone else is saying the same thing, so if I’m fooling myself then we’re all fooling ourselves, right? And there is a lot to be said for the wisdom of crowds that will be addressed in a future blogpost. The long-running IPF consensus forecasts is a rich resource when considering this within a real estate context. Each quarter multiple forecasts for the UK real estate market are collated and published. Comparing the absolute error in consensus five-year total return forecasts versus the outturn highlights where these forecasts have gone awry since 2006, and unfortunately proves that crowds are far from infallible.

The analysis shows that consensus was at times up to 5% pa above or below the outturn – and often for an extended period of time. Individual forecasters may have done better than consensus over this period, although I’d wager that few of them were able to do so on a consistent basis.

Similarly, anyone familiar with the LIBOR/SONIA forward curve ‘hairy’ chart knows that the outlook for the cost of borrowing implied by the financial market is wrong far more frequently than it is ever right.

Regardless, it does appear as if a consensus outlook – wrong as it frequently was - provided more guidance than a one-dimensional view. An assumption that the next five years play out exactly as the last five years – what econometricians call a simple forecast – fares much worse than the IPF consensus. Interestingly, using an adapted simple forecast where we compare the last 3 years with the next 5 years, proves just as accurate as IPF consensus. So for those of you without access to forecasts, just look back at what happened over the last three years.

As an aside and as would be expected, this adapted simple forecast results in broadly equal proportions of over and under estimations (52:48). By contrast, IPF consensus highlights humans’ intrinsic loss aversion (42:58) – another behavioural bias worth being aware of.

“If you are always trying to be normal, you will never know how amazing you can be”, Maya Angelou

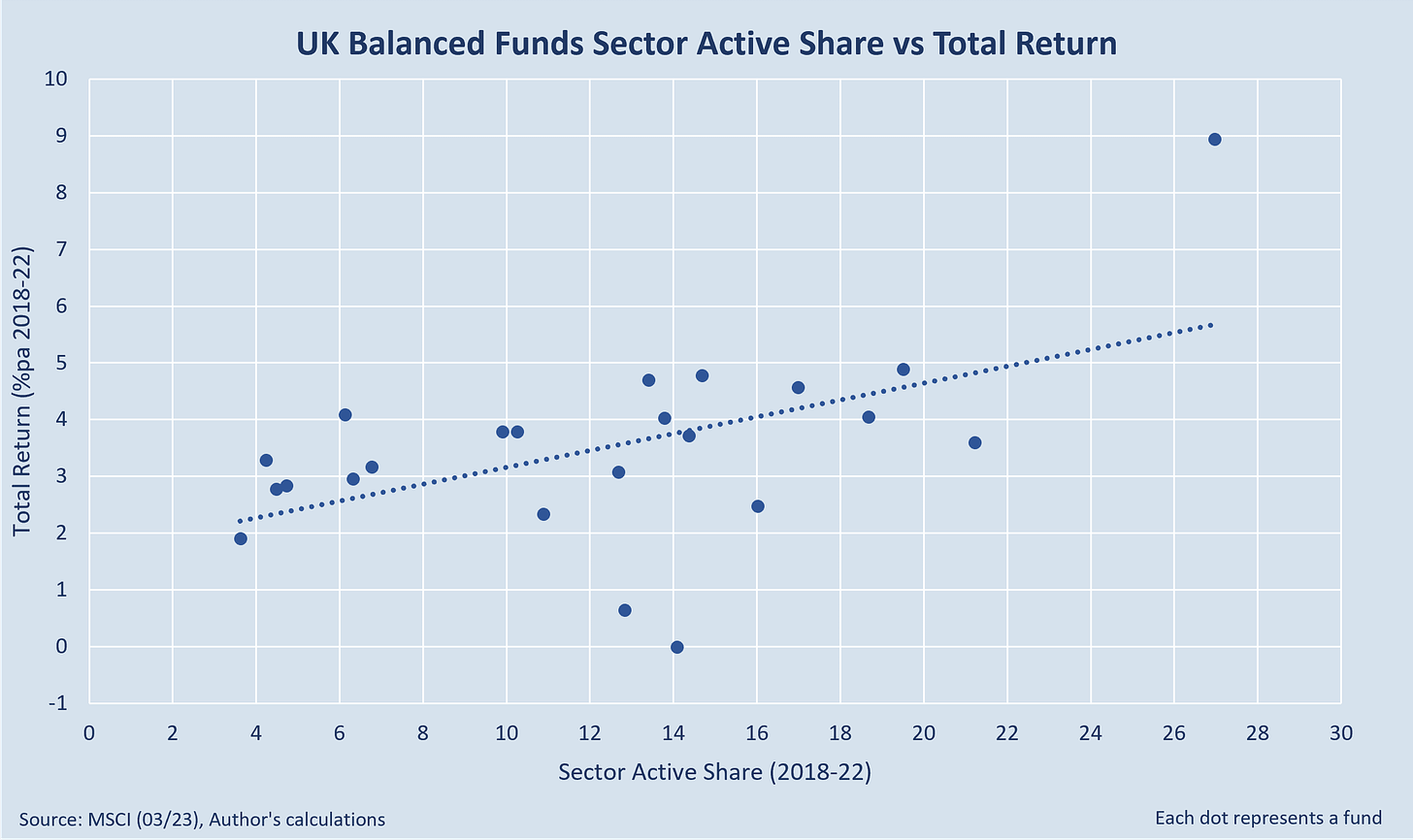

Herd mentality can also be constraining. Relative investors will also know that – however accurate a forecast may be - in order to outperform a benchmark, one has to deviate from it through at least one factor. For example, there is an observable positive correlation between outperformance of AREF/MSCI UK balanced real estate funds and both their sector active share and concentration.

And yet, the fear of looking stupid is a powerful motivator, and so there is comfort in not straying far from consensus. This may be with a view to limiting downside risks, which is a perfectly valid investment strategy. The salient point here that is often missed is that the investors should be aware of the natural biases they have and the position they are taking. If they are not, then they may be unduly sacrificing performance.

“Please tell me something I don’t know”, The Wolf of Wall Street

We’ve barely scratched the surface of three common biases within behavioural finance. But already we can see that these biases are intrinsic and often unquantifiable. The first step to mitigate them is simply to be aware of them. When it comes to investment decisions, biases need to be priced in as far as possible, alongside the more traditional measures of risk, such as volatility and uncertainty. Many companies rightly require that their employees undergo mandatory Unconscious Bias training, to reduce discrimination, and promote inclusivity & diversity. If only they did the same for Behavioural Finance Bias too.